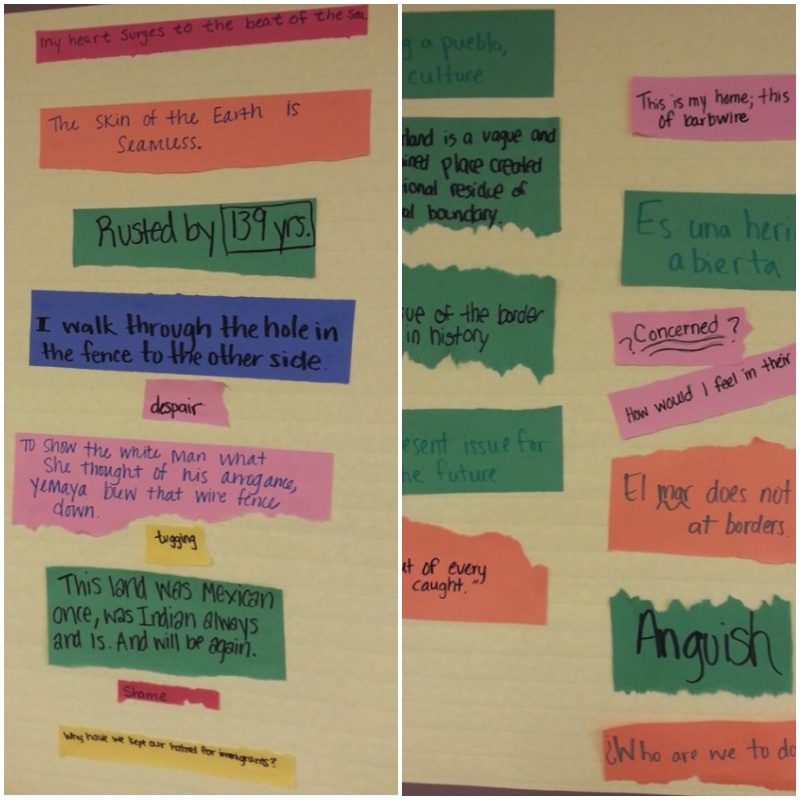

-“Found Poems” students in my 420/520 course made. To make “Found Poems,” students are asked to write down key words or phrases that describe what they learned, felt, or wondered about drawing across that week’s assigned readings. The words or phrases have to come directly from the assigned readings. Students write these down on slips of paper, add these to a collective course pile, and then these are randomly distributed to groups. The groups have to then create a “Found Poem” using the slips of paper they’ve been randomly given. Groups read these out loud and we then use these to launch into a fuller discussion of that week’s themes. These images reflect their reading of Anzaldúa’s El Aztlán/El Otro México.

– The course presently titled “Bilingualism and the Education of Latinx Youth” and recently taught by Dr. Noreen Naseem Rodríguez was first offered in 2005 under the title of “Bilingualism, Bilingual Education, and US Mexican Youth” by Dr. Katherine Bruna who designed it upon her arrival from California in 2003. This offering represents an exciting example of the ways our classes change to include national shifts in the way we engage history and learning. The class was offered in the Fall of 2020, and here is a link to some of the projects students completed in the past: https://usls.las.iastate.edu/2021/04/27/usls-educ-420-520-student-projects/

We are pleased to share an honest reflection from Dr. Bruna below.

– I designed the SOE 420/520 course as a new faculty member, shortly after arriving at ISU from California in 2003. I first taught it in 2005 and taught it every Fall semester until 2020. The original title was “Bilingualism, Bilingual Education, and US Mexican Youth.” The title reflected the experience I was bringing as a U.S. Department of Bilingual Education Doctoral Fellow and the postdoctoral work I did at the American Institutes of Research evaluating professional development institutes that were legislated in California after the passage of Proposition 227, the “English-Only” bill. This bill made English Only the default option for linguistically-minoritized youth and essentially undermined years of bilingual education programming in California. As a result of the bill, students who would otherwise have been placed in bilingual classrooms now were placed in English immersion settings with teachers who didn’t have adequate preparation or experience. My post-doc work was to evaluate the state-mandated professional development institutes that all teachers had to attend. I was able to observe the training of teachers of all grade levels across all content areas for English Language Development work. Because of the California setting and as a result of my own interest and experience (B.A. in Hispanic Studies and work with Mexican youth and families in migrant camps), I was particularly interested in the Mexican (im)migrant student audience. And, coming to ISU, I had my eye on the context of Iowa’s demographically-transitioning communities and the wave of Mexican (im)migration the state was experiencing at that time, post-NAFTA. So this course was a place to import these experiences and expertise and also connect that to the research agenda I was establishing on the experience of newcomer US Mexican youth in the classrooms of these rapidly-changing communities, which also involved work in the sending communities of rural Mexico. The focus on US Mexican youth reflected the well-documented particularities of the Mexican experience that are lost when otherwise subsumed under a pan-ethnic Hispanic/Latinx label). And in “US Mexican” the hyphen was deliberately missing so the connection between the US and Mexico would be unbounded and inclusive of hybrid cultural identities as well as descriptive of mere binational migration networks – easier before the amping up of anti-immigrant sentiment and the clamor for a tighter border.

– I launched the course by using Anzaldúa’s El Aztlan/El Otro Mexico to introduce the idea of borderlands, borders, bordered identity, and transcultural and linguistic positioning and, in general, teach a much-needed history with implications for grasping current anti-immigrant discourse. We read ethnographic accounts of the US Mexican experience in classrooms and communities, with a focus on the Midwest. We examine our own learning experiences and stereotypes and where these come from. A focus is understanding the social and schooling causes of socioeconomic disparity, particularly as related to language and language identity.

– We then turn to school policy and practice and the important difference between the ESL and Bilingual paradigms. We read teacher-generated accounts of work in bilingual classrooms , observe bilingual education formats and practices, and reflect on the use of strategies, such as translanguaging, in our future classrooms or other professional contexts. Students develop expertise on a related topic of their own interest, share that with their peers, and develop an action plan for their work as future bilingual education advocates and responsive teachers/community members of/with US Mexican students. The course satisfies the sociolinguistics requirement for the ESL endorsement at ISU. It is also an option for the Social Justice Certificate. You don’t need to be a future teacher to take the course, but interested in language, culture, and identity more generally.

– In 2020, the course title changed to “Bilingualism and the Education of Latinx youth.” This reflected the expanded capacity in the SOE for the course to be taught by Latinx-identified scholars and interest in a population broader than my original focus.

– Historically, the course’s emergence really reflects what was happening in Iowa and around the Midwest in the early 2000s, with more direct-to-Iowa (im)migration from Mexico as opposed to movement through and from traditional “gateway” states, such as California or Texas. It helped prepare future teachers to understand and respond to the experience of US Mexican youth and families as part of that phenomena. That movement slowed, given the recent political climate and immigration policies, but there are continuing challenges in providing equitable educational opportunities to youth from families with connections to Latin American countries of origin, and so the course will remain relevant in helping future teachers, or advocates more generally, meet those needs.

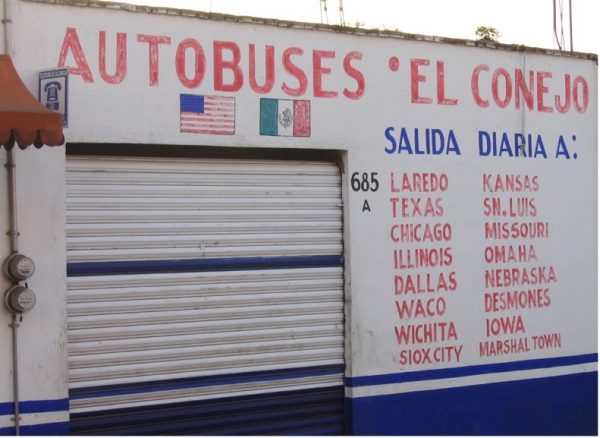

– The bus station in Puruándiro, Michoacán, México listing daily departures to several Iowa and Midwest locations. Richardson Bruna asks students to analyze images like this one, from her fieldwork, for what they reveal about Mexico-US migration, transnational identity, and education in the “New Latinx Diaspora.” Photo by Katherine Richardson Bruna circa 2006.